Induction Hardening Surface Process Applicatons

What is induction hardening ?

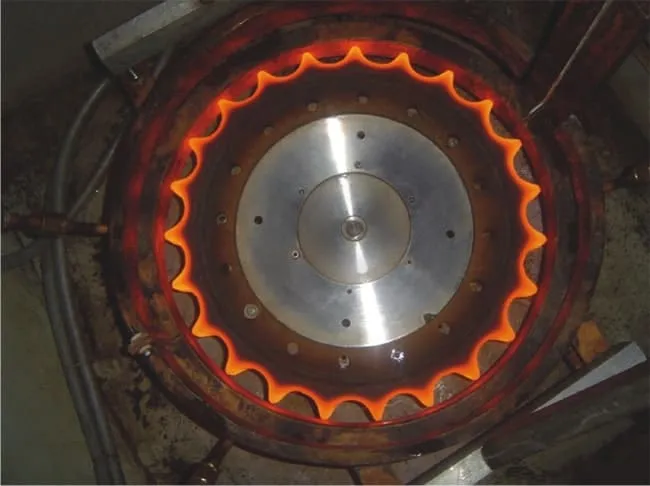

Induction hardening is a form of heat treatment in which a metal part with sufficient carbon content is heated in the induction field and then rapidly cooled. This increases both the hardness and brittleness of the part. Induction heating allows you to have localized heating to a pre-determined temperature and enables you to precisely control the hardening process. Process repeatability is thus guaranteed. Usually, induction hardening is applied to metal parts which need to have great surface wear resistance, while at the same time retaining their mechanical properties. After the induction hardening process is achieved, the metal workpiece needs to be quenched in water, oil or air inorder to obtain specific properties of the surface layer. Induction hardening is a method of quickly and selectively hardening the surface of a metal part. A copper coil carrying a significant level of alternating current is placed near (not touching) the part. Heat is generated at, and near the surface by eddy current and hysteresis losses. Quench, usually water-based with an addition such as a polymer, is directed at the part or it is submerged. This transforms the structure to martensite, which is much harder than the prior structure.

A popular, modern type of induction hardening equipment is called a scanner. The part is held between centers, rotated, and passed through a progressive coil which provides both heat and quench. The quench is directed below the coil, so any given area of the part is rapidly cooled immediately following heating. Power level, dwell time, scan (feed) rate and other process variables are precisely controlled by a computer.

Case hardening process used to increase wear resistance, surface hardness and fatigue life through creation of a hardened surface layer while maintaining an unaffected core microstructure.

Induction hardening is a method of quickly and selectively hardening the surface of a metal part. A copper coil carrying a significant level of alternating current is placed near (not touching) the part. Heat is generated at, and near the surface by eddy current and hysteresis losses. Quench, usually water-based with an addition such as a polymer, is directed at the part or it is submerged. This transforms the structure to martensite, which is much harder than the prior structure.

A popular, modern type of induction hardening equipment is called a scanner. The part is held between centers, rotated, and passed through a progressive coil which provides both heat and quench. The quench is directed below the coil, so any given area of the part is rapidly cooled immediately following heating. Power level, dwell time, scan (feed) rate and other process variables are precisely controlled by a computer.

Case hardening process used to increase wear resistance, surface hardness and fatigue life through creation of a hardened surface layer while maintaining an unaffected core microstructure.

Processes and Industries that can benefit from induction hardening:

-

Heat-treatment

-

Chain hardening

-

Tube & Pipe Hardening

-

Shipbuilding

-

Aerospace

-

Railway

-

Automotive

-

Renewable energies

Benefits of Induction Hardening:

Favoured for components that are subjected to heavy loading. Induction imparts a high surface hardness with a deep case capable of handling extremely high loads. Fatigue strength is increased by the development of a soft core surrounded by an extremely tough outer layer. These properties are desirable for parts that experience torsional loading and surfaces that experience impact forces. Induction processing is performed one part at a time allowing for very predictable dimensional movement from part to part.-

Precise control over temperature and hardening depth

-

Controlled and localized heating

-

Easily integrated into production lines

-

Fast and repeatable process

-

Each workpiece can be hardened by precise optimized parameters

-

Energy-efficient process

Steel and stainless-steel components that can be hardened with induction:

Fasteners, flanges, gears, bearings, tube, inner and outer races, crankshafts, camshafts, yokes, drive shafts, output shafts, spindles, torsion bars, slewing rings, wire, valves, rock drills, etc.

Increased Wear Resistance

There is a direct correlation between hardness and wear resistance. The wear resistance of a part increases significantly with induction hardening, assuming the initial state of the material was either annealed, or treated to a softer condition.Increased Strength & Fatigue Life due to the Soft Core & Residual Compressive Stress at the Surface

The compressive stress (usually considered a positive attribute) is a result of the hardened structure near the surface occupying slightly more volume than the core and prior structure.Parts may be Tempered after Induction Hardening to Adjust Hardness Level, as desired

As with any process producing a martensitic structure, tempering will lower hardness while decreasing brittleness.Deep Case with Tough Core

Typical case depth is .030” - .120” which is deeper on average than processes such as carburizing, carbonitriding, and various forms of nitriding performed at sub-critical temperatures. For certain projects such as axels, or parts which are still useful even after much material has worn away, case depth may be up to ½ inch or greater.Selective Hardening Process with No Masking Required

Areas with post-welding or post-machining stay soft - very few other heat treat processes are able to achieve this.Relatively Minimal Distortion

Example: a shaft 1” Ø x 40” long, which has two evenly spaced journals, each 2” long requiring support of a load and wear resistance. Induction hardening is performed on just these surfaces, a total of 4” length. With a conventional method (or if we induction hardened the entire length for that matter), there would be significantly more warpage.Allows use of Low Cost Steels such as 1045

The most popular steel utilized for parts to be induction hardened is 1045. It is readily machinable, low cost, and due to a carbon content of 0.45% nominal, it may be induction hardened to 58 HRC +. It also has a relatively low risk of cracking during treatment. Other popular materials for this process are 1141/1144, 4140, 4340, ETD150, and various cast irons.Limitations of Induction Hardening

Requires an Induction Coil and Tooling which relates to the Part’s Geometry

Since the part-to-coil coupling distance is critical to heating efficiency, the coil’s size and contour must be carefully selected. While most treaters have an arsenal of basic coils to heat round shapes such as shafts, pins, rollers etc., some projects may require a custom coil, sometimes costing thousands of dollars. On medium to high volume projects, the benefit of reduced treatment cost per part may easily offset coil cost. In other cases, the engineering benefits of the process may outweigh cost concerns. Otherwise, for low volume projects the coil and tooling cost usually makes the process impractical if a new coil must be built. The part must also be supported in some manner during the treatment. Running between centers is a popular method for shaft type parts, but in many other cases custom tooling must be utilized.Greater Likelihood of Cracking Compared to most Heat Treatment Processes

This is due to the rapid heating and quenching, also the tendency to create hot spots at features/edges such as: keyways, grooves, cross holes, threads.Distortion with Induction Hardening

Distortion levels do tend to be greater than processes such as ion or gas nitriding, due to the rapid heat/quench and resultant martensitic transformation. That being said, induction hardening may produce less distortion than conventional heat treat, particularly when it’s only applied to a selected area.Material Limitations with Induction Hardening

Since the induction hardening process does not normally involve diffusion of carbon or other elements, the material must contain enough carbon along with other elements to provide hardenability supporting martensitic transformation to the level of hardness desired. This typically means carbon is in the 0.40%+ range, producing hardness of 56 – 65 HRC. Lower carbon materials such as 8620 may be used with a resultant reduction in achievable hardness (40-45 HRC in this case). Steels such as 1008, 1010, 12L14, 1117 are typically not used due to the limited increase in hardness achievable.Induction Hardening Surface Process details

Induction hardening is a process used for the surface hardening of steel and other alloy components. The parts to be heat treated are placed inside a copper coil and then heated above their transformation temperature by applying an alternating current to the coil. The alternating current in the coil induces an alternating magnetic field within the work piece which causes the outer surface of the part to heat to a temperature above the transformation range. The components are heated by means of an alternating magnetic field to a temperature within or above the transformation range followed by immediate quenching. It is an electromagnetic process using a copper inductor coil, which is fed a current at a specific frequency and power level.